Excerpt from the story One Man’s Journey From Bladder Cancer

The day for my fourth cystoscopy had finally arrived. My doctor smiled and asked if I was ready for this exam. With a nod from me, turned off the lights, and guided the instrument into my body. He reiterated that there were cells in my bladder. I felt a large lump in my throat, and my face began to flush. Because these cells had been so aggressive and returned after the three previous treatments, there were no additional medications that could be used. He explained there were several other choices: (1) do nothing, (2) having a neo-bladder constructed, and (3) urostomy surgery. We would discuss these options in a few weeks.

The day for my fourth cystoscopy had finally arrived. My doctor smiled and asked if I was ready for this exam. With a nod from me, turned off the lights, and guided the instrument into my body. He reiterated that there were cells in my bladder. I felt a large lump in my throat, and my face began to flush. Because these cells had been so aggressive and returned after the three previous treatments, there were no additional medications that could be used. He explained there were several other choices: (1) do nothing, (2) having a neo-bladder constructed, and (3) urostomy surgery. We would discuss these options in a few weeks.

Note: Each person is unique, and so are the methods used to treat this cancer.

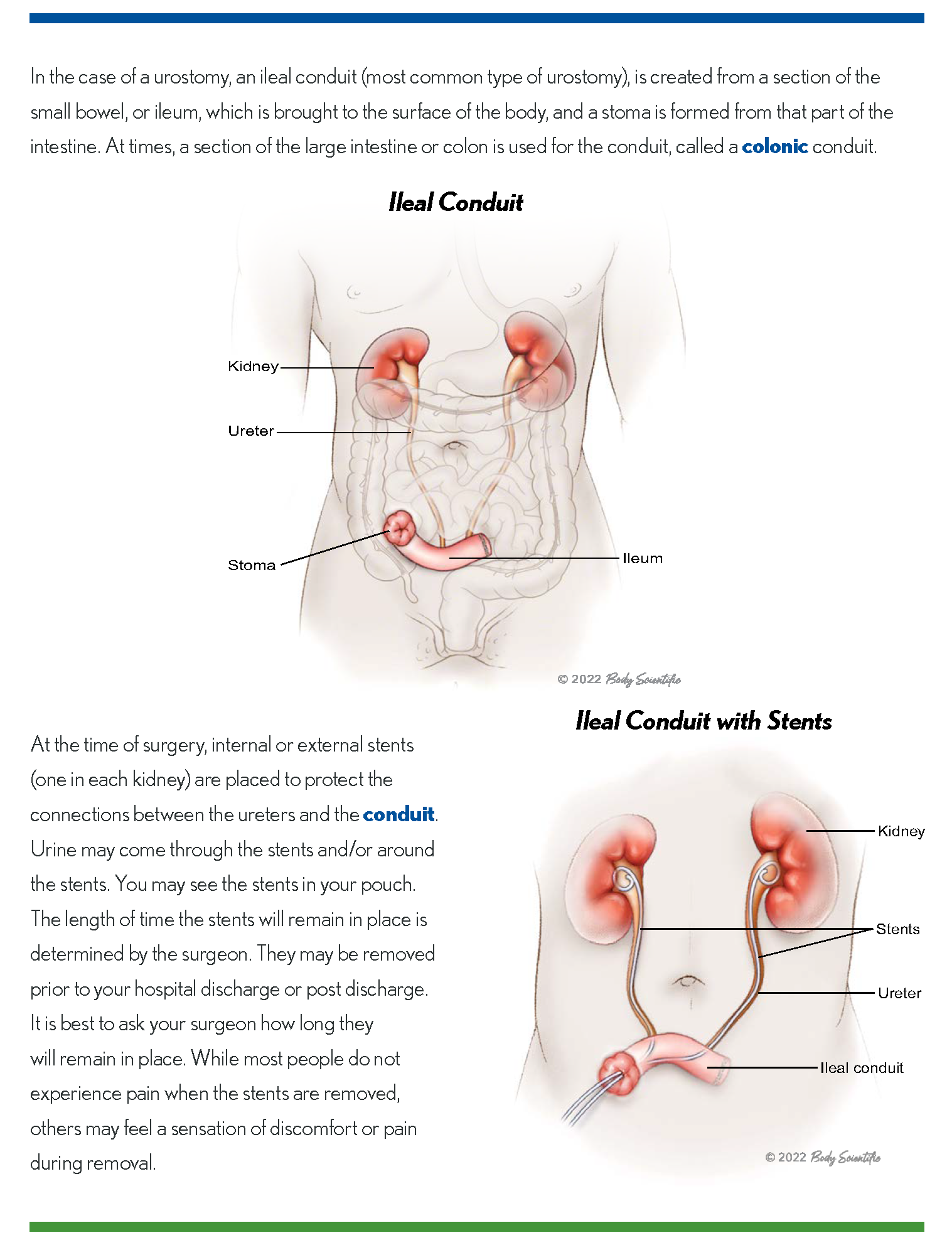

An appointment was made for this consultation, and within two weeks I would see my doctor. In the interim, I had given careful thought to all three options. Doing nothing could be taking a huge risk. If the cells should travel into the muscles of the bladder, my life would definitely be in jeopardy. There was a chance these cells might metastasize to other organs of my body. We could wait and see if they did travel. However, this was not a chance I wanted to take. A neo-bladder, created from my intestines, would allow me to still urinate through my penis, but required much effort to adjust to, and a longer recovery time. It also brought with it the possibility of incontinence, or not working properly, necessitating additional surgery. The neo-bladder is also a relatively new form of treatment that many urologists choose not to use.

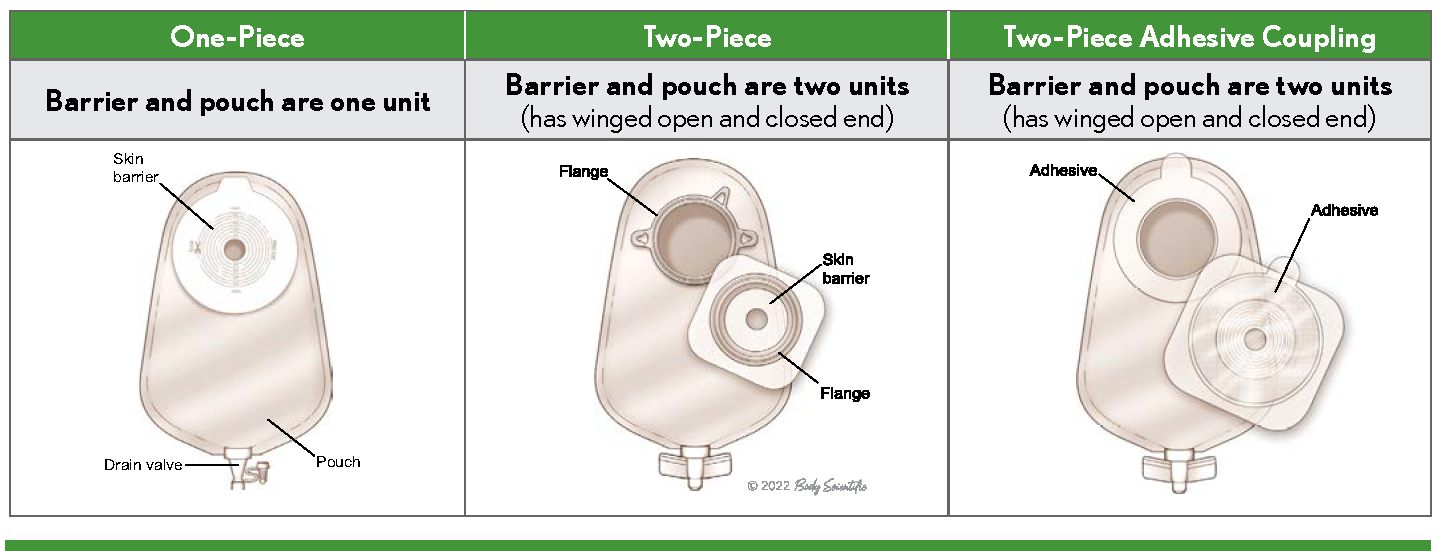

My final option was to have my bladder and prostate gland removed surgically. Compared to the construction of a neo-bladder, the recovery time was shorter. It had been proven to be successful in eliminating cancer and allowing patients to resume normal lives. This return to normalcy would occur after an initial adjustment period when the patient learns how to use and care for the Ostomy Pouch. Over time this would become routine.

After more consultation… My faith and confidence in my physician and in my decision to receive “external plumbing” (the ostomy pouch), gave me peace of mind up to the day of surgery.

Road to Recovery

My hospitalization would soon be terminating. However, before leaving I insisted on seeing the Ostomy Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) making sure that I felt confident applying and removing my ostomy pouch. Even though the hospital wanted to discharge me, I was persistent. Managing my ostomy pouch will be a lifelong endeavor. The CNS reviewed the process of changing the pouch and demonstrated it several times. Her patience, warm smile and reassurance made me feel capable of handling this task on my own and confident to be discharged from the hospital. (Keep in mind that it is a patient’s right to determine whether or not he/she is ready to leave the hospital)

On My Own

After then spending time in a rehabilitation facility It was great to finally be home, and feel independent. As a widower, I was fortunate enough to have met a woman whose companionship helped to avoid a great deal of loneliness. Had she not been there, returning to my empty house would have heightened my feeling of isolation. Thinking back, yes, I certainly could have managed by myself. However, her presence made my transition from the hospital, rehabilitation facility, to home that much easier. Many patients who are single, or don’t have family/friends to support them when returning home, can find this a mixed blessing. They may feel independent, yet experience loneliness. Anxiety may occur over fear they may lack the ability to manage by themselves. The services of a visiting nurse, physical/occupational therapist, or a mental health professional can be provided to alleviate these concerns. The availability of these services were discussed during my exit conference from the rehabilitation center.

Adjustments To Be Made

Anxiety arose as I continued on my journey to recovery. The first of these emotional hurdles, especially for newbies is attaching an ostomy bag securely, preventing leakage. Having a spare pouch and supplies, along with a change of clothes, solves this concern. My medical supplier provided a small pouch to carry these items. Initially, I had many questions about the ostomy pouch. However, when various concerns arose, (getting this device on properly, leaks, or supplies), my nurse responded to these questions promptly and gave me the reassurance I needed. Trust me, I continued to have questions for months after my surgery. By that time I built up enough confidence in using this device, and it became more routine. Ostomy nurses serve as a great resource. They also recommended a monthly support group. Knowing what others have gone through, and how they dealt with their post-surgical life, can be very helpful.

pouch and supplies, along with a change of clothes, solves this concern. My medical supplier provided a small pouch to carry these items. Initially, I had many questions about the ostomy pouch. However, when various concerns arose, (getting this device on properly, leaks, or supplies), my nurse responded to these questions promptly and gave me the reassurance I needed. Trust me, I continued to have questions for months after my surgery. By that time I built up enough confidence in using this device, and it became more routine. Ostomy nurses serve as a great resource. They also recommended a monthly support group. Knowing what others have gone through, and how they dealt with their post-surgical life, can be very helpful.

Thanks to my Ostomy Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS), two additional Leak Prevention Supplies (LPS) were suggested: (1) A belt attaching to both sides of the bag to hold the wafer and pouch more securely in place, and (2) A U-shaped elastic barrier fitting around the bottom of the adhesive which attaches to your body and wafer. These items can be requested from your medical supplier, and may help give some peace of mind. These remedies have worked for me. Timing for emptying the pouch is another adjustment. This usually occurs when the bag is 1/3 to 1/2 full. For me, this point is reached hourly, possibly because my kidneys are located in the front of my body. For others, this may occur up to 2 1/2 hours. However, empty points are individualized.

Timing this process initially limited me from going places beyond one hour. For many of us, noting the location of bathrooms is something we typically make prior to leaving for a destination. Even before surgery, I spotted the location of the bathrooms. If you think about it, for many people who still have their bladder, nature calls them frequently. Whenever this need arises, they go on “bathroom alert.” We don’t have this urgency or stress of finding a bathroom as they do. We can anticipate when to empty our pouch and can plan our pit stops in advance. This is a positive of having an ostomy pouch. Think about that.

Ways to judge the timing of emptying the pouch also become routine. Checking your watch, cell phone, or clock helps the timing factor. Generally, If I were to go to a restaurant, at most, twenty minutes away from home, I’m able to wait until I have eaten my meal before emptying my bag. For others, gauging the timing may involve the length of events (movies, shows, etc.) or the time it takes to reach a destination. It’s an awareness that you will develop. During your recovery period, fatigue could be an issue. Initially, I tried to do too much, too soon. Don’t fight this feeling. You don’t have to prove anything to yourself or anyone else, about how well you are recovering. Listen to your body. If it’s telling you to rest, do that. Remember, the fatigue lessens over time, and your strength does return. For me, it took approximately four months.

Don’t Try to push yourself. If you do you might become frustrated and that doesn’t help. In fact it may extend your recovery time.

Pouch Changing 101

I had devised my own schedule for changing the ostomy pouch — every Friday and Monday. A rule of thumb is to change it every three-four days. You will decide what days, how often, as well as choosing a medical supplier that offers products that best suits your needs. After leaving rehab, one company had offered supplies to me. If you, like me, prefer their products, then stick with them. If not, check other distributors and request samples from them. Many people experiment with several companies before finding the products that work for them.

After experiencing a few glitches, (ie; tearing a pouch, or unable to remove the protective piece covering the wafer),you realize some possibly could be avoided in the future. Being aware of these mishaps helps to avoid future problems, and will make the process of changing your bag go more smoothly. In addition, once you have repeatedly gone through this part of your “life without a bladder” it doesn’t require too much thinking or time. Perhaps this thought may be difficult to believe, but it does happen.

Don’t get bent out of shape when things don’t go as planned. Use these experiences as problems to be solved.

You may find other obstacles to overcome. The good news, once these challenges are met and conquered, they make this part of your life more tolerable. It may seem as though you’ll never feel comfortable. The more you are aware of this process, and follow it repeatedly, the easier it is to make the required adjustments. Those who have traveled along this path can be very helpful. They have been for me. The more information you receive, the less stress you will experience.

Be patient with yourself don’t hesitate to ask any questions you may have.

Yes, there are adjustments to make and new roads to travel. Through knowledge gained from resources, along with your own experiences, make this continuing journey just another routine part of your life. However, it takes time and effort. HAVE PATIENCE!!

It has been several years since my surgery. I have learned a lot, and have made adjustments to my life. You can reach this point as well.

YES, THIS IS SOMETHING YOU NEVER EXPECTED. YES, THERE ARE ADJUSTMENTS YOU WILL NEED TO MAKE. YES, THIS PROCESS TAKES TIME. YES, THIS WILL BECOME ANOTHER ROUTINE PART OF YOUR LIFE.

The day for my fourth cystoscopy had finally arrived. My doctor smiled and asked if I was ready for this exam. With a nod from me, turned off the lights, and guided the instrument into my body. He reiterated that there were cells in my bladder. I felt a large lump in my throat, and my face began to flush. Because these cells had been so aggressive and returned after the three previous treatments, there were no additional medications that could be used. He explained there were several other choices: (1) do nothing, (2) having a

The day for my fourth cystoscopy had finally arrived. My doctor smiled and asked if I was ready for this exam. With a nod from me, turned off the lights, and guided the instrument into my body. He reiterated that there were cells in my bladder. I felt a large lump in my throat, and my face began to flush. Because these cells had been so aggressive and returned after the three previous treatments, there were no additional medications that could be used. He explained there were several other choices: (1) do nothing, (2) having a  pouch and supplies, along with a change of clothes, solves this concern. My medical supplier provided a small pouch to carry these items. Initially, I had many questions about the ostomy pouch. However, when various concerns arose, (getting this device on properly, leaks, or supplies), my nurse responded to these questions promptly and gave me the reassurance I needed. Trust me, I continued to have questions for months after my surgery. By that time I built up enough confidence in using this device, and it became more routine. Ostomy nurses serve as a great resource. They also recommended a monthly support group. Knowing what others have gone through, and how they dealt with their post-surgical life, can be very helpful.

pouch and supplies, along with a change of clothes, solves this concern. My medical supplier provided a small pouch to carry these items. Initially, I had many questions about the ostomy pouch. However, when various concerns arose, (getting this device on properly, leaks, or supplies), my nurse responded to these questions promptly and gave me the reassurance I needed. Trust me, I continued to have questions for months after my surgery. By that time I built up enough confidence in using this device, and it became more routine. Ostomy nurses serve as a great resource. They also recommended a monthly support group. Knowing what others have gone through, and how they dealt with their post-surgical life, can be very helpful.